On January 7, 2025, wildfires erupted in Southern California, continuing for 24 days and involving more than 37,000 acres of land. These recent wildfires have highlighted the increasing population affected by climate-related respiratory events.1,2

In addition to immediate loss of human lives and property, wildfires significantly increase outdoor levels of air pollution, including small particulate matter, which has been linked to increased respiratory exacerbations and decline in lung function.3 Air pollution is receiving increasing attention as an attributable risk factor for both asthma and COPD, and populations with these diseases experience significant health risks during wildfire events.3,4 Outdoor air pollution—including increases associated with wildfires—has been associated with impaired lung development in children, adolescents, and young adults, providing possible pathways to adult morbidity, including asthma, COPD, chronic bronchitis, and lung cancer.5–7

Wildfires are not the only climate-related respiratory exposure faced by patients. Extensive flooding, like that caused by a tropical storm in Western North Carolina, is associated with significant increases in mold exposure, exposures of water contaminants, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and other respiratory risk factors.8 Droughts, temperature changes, and increased aeroallergens are other climate-related exposures linked to respiratory health.1

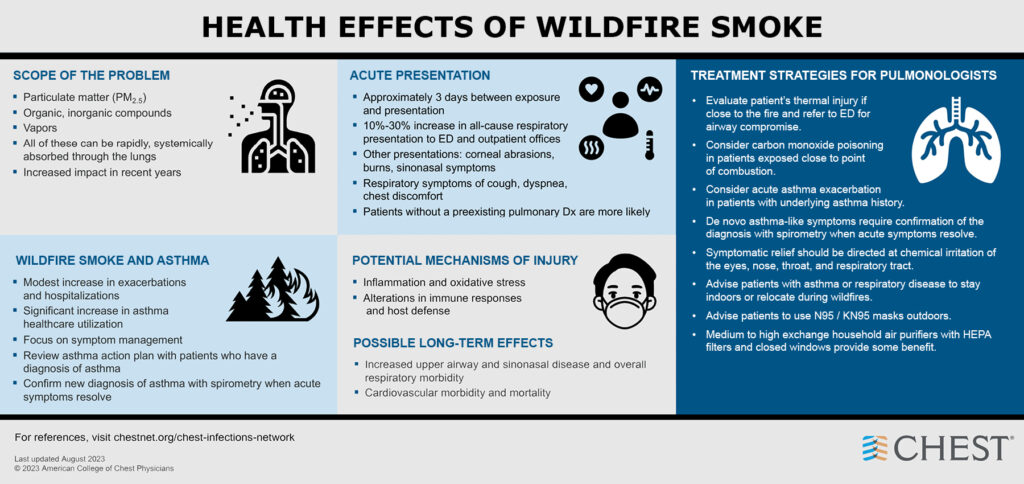

While relatively little is known about how to best prevent and treat climate-related respiratory health events, the Chest Infections and Disaster Response Network at CHEST did previously create a resource for the management of wildfire-related respiratory events (see image below).

In addition to previously published resources such as this one, we suggest six possible steps a pulmonary clinician can take prior to a climate-related event.

- Monitor climate events: Awareness of climate-related events can inform clinical practice, and the effects of distant events may be felt locally later.

- Familiarize yourself with local climate and air quality resources: Air quality indices that can be used to inform clinicians and patients of air quality events are available online. Airnow.gov displays local data, and many states publish complimentary data and alerts through public health departments.

- Review clinical guidance where available: The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) offers training for clinicians related to particle pollution, which has bearing on areas surrounding wildfires. National conferences are increasingly offering clinical resources for climate-related events.

- Review health system preparedness measures: Climate events such as wildfires are associated with increased health care utilization, as shown above. Analytics can be considered by health care systems to prepare for increased utilization.

- Incorporate air pollution exposures and climate-related events into clinical histories: Environmental exposures and climate-related events can be associated with the development of future pulmonary disease and increased disease exacerbations.

- Engage in preventative conversations with patients at risk: Basic preventative measures can be implemented prior to climate-related events to decrease individual patient risk, including planned limitation of outdoor exposure. Education on the impact of climate-related exposures, the role of exposure avoidance, and the role of indoor climate control through air filtration may help prepare for unexpected climate events. The EPA provides guidance on home air filtration as well as affordable homemade options.

References

1. Lewy JR, Karim AN, Lokotola CL, et al. The impact of climate change on respiratory care: a scoping review. The Journal of Climate Change and Health. 2024;17:100313.

2. Keswani A, Akselrod H, Anenberg SC. Health and clinical impacts of air pollution and linkages with climate change. NEJM Evid. 2022;1(7):EVIDra2200068.

3. Skinner R, Luther M, Hertelendy AJ, et al. A literature review on the impact of wildfires on emergency departments: enhancing disaster preparedness. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2022;37(5):657-664.

4. Noah TL, Worden CP, Rebuli ME, Jaspers I. The effects of wildfire smoke on asthma and allergy. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2023;23(7):375-387.

5. Garcia E, Birnhak ZH, West S, et al. Childhood air pollution exposure associated with self-reported bronchitic symptoms in adulthood. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2024;210(8):1025-1034.

6. Marott JL, Ingebrigtsen TS, Çolak Y, Vestbo J, Lange P. Lung function trajectories leading to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as predictors of exacerbations and mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(2):210-218.

7. Korsiak J, Pinault L, Christidis T, Burnett RT, Abrahamowicz M, Weichenthal S. Long-term exposure to wildfires and cancer incidence in Canada: a population-based observational cohort study. Lancet Planet Health. 2022;6(5):e400-e409.

8. Johanning E, Auger P, Morey PR, Yang CS, Olmsted E. Review of health hazards and prevention measures for response and recovery workers and volunteers after natural disasters, flooding, and water damage: mold and dampness. Environ Health Prev Med. 2014;19(2):93-99.